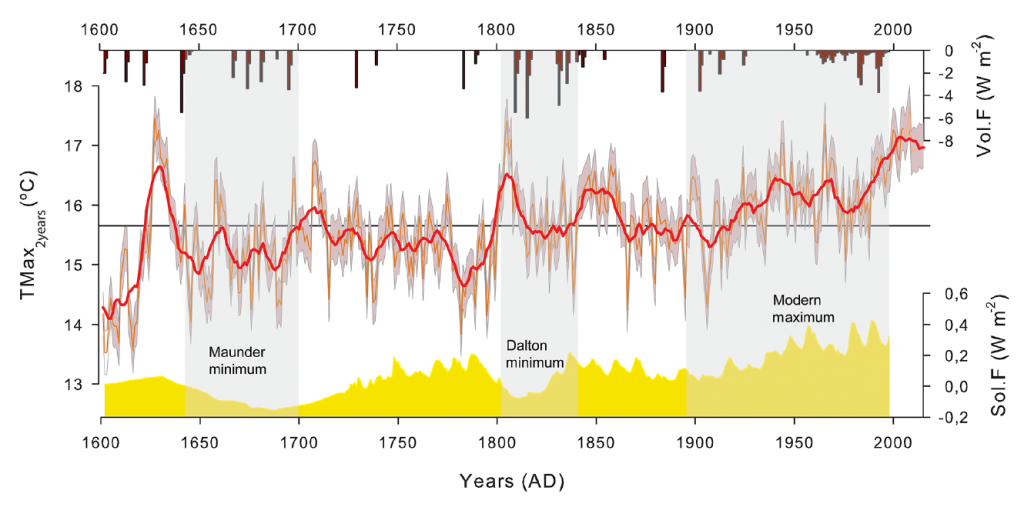

Beeinflusst die Sonne das Klima? Im heutigen Beitrag wollen wir neue Studien aus Spanien und Portugal vorstellen, die hier Licht ins Dunkel bringen. Im Februar 2017 erschien in Climate of the Past eine Baumring-Studie einer Gruppe um Ernesto Tejedor, in der eine Temperaturrekonstruktion für die Iberische Halbinsel für die vergangenen 400 Jahre vorgestellt wird. Die Autoren heben hervor, dass die Temperaturschwankungen recht gut mit den Schwankungen der Sonnenaktivität zusammenpassen. Warme Phasen gehen dabei mit Zeiten erhöhter Sonnenaktivität einher. Insgesamt hat sich das Untersuchungsgebiet in diesen 400 Jahren um fast 3°C erwärmt, was den Übergang von der Kleinen Eiszeit zur Modernen Wärmeperiode widerspiegelt (Abb.). Allerdings gab es bereits um 1625 und 1800 Phasen, als die Temperaturen für kurze Zeit das heutige Niveau erreichten.

Abbildung: Temperaturentwicklung im Gebirgszug Nordspanien während der letzten 400 Jahre und Vergleich mit der Sonnenaktivität. Quelle: Tejedor et al. 2017.

Hier der Abstract der Studie:

Temperature variability in the Iberian Range since 1602 inferred from tree-ring records

Tree rings are an important proxy to understand the natural drivers of climate variability in the Mediterranean Basin and hence to improve future climate scenarios in a vulnerable region. Here, we compile 316 tree-ring width series from 11 conifer sites in the western Iberian Range. We apply a new standardization method based on the trunk basal area instead of the tree cambial age to develop a regional chronology which preserves high- to low-frequency variability. A new reconstruction for the 1602–2012 period correlates at −0.78 with observational September temperatures with a cumulative mean of the 21 previous months over the 1945–2012 calibration period. The new IR2Tmax reconstruction is spatially representative for the Iberian Peninsula and captures the full range of past Iberian Range temperature variability. Reconstructed long-term temperature variations match reasonably well with solar irradiance changes since warm and cold phases correspond with high and low solar activity, respectively. In addition, some annual temperature downturns coincide with volcanic eruptions with a 3-year lag.

Weiter gehts in Portugal. Anna Morozova und Tatiana Barlyaeva analysierten den Temperaturverlauf der letzten 100 Jahre in Lissabon, Coimbra und Porto. Dabei stießen sie auf ein schwaches aber statistisch gut abgesichertes Signal der 11- und 22-jährigen Sonnenzyklen in den Temperaturdaten. Im Haupttext ihrer Arbeit heißt es dazu:

Weak but statistically significant (bi-)decadal signals in the temperature series that can be associated with the solar and geomagnetic activity variations were found. These signals are stronger during the spring and autumn seasons. The multiple regression models which include the sunspot numbers or the geomagnetic indices among other regressors have higher predictionquality. The wavelet coherence analysis shows that there are time lags between the temperature variations and the solar activity cycles. These lags are about 1–2 years in case of the 11-yr solar cycle as well as in case of the 22-yr solar magnetic cycle (relatively to the solar polar magnetic field observations). These lags are confirmed by the correlation analysis. The results obtained by these methods as well as comparison to results of other studies allow us to conclude that the found (bi-)decadal temperature variability modes can be associated, at least partly, with the effect of the solar forcing.

Bleiben wir in Portugal, gehen aber auf den weiten Atlantischen Ozean hinaus. Die Inselgruppe der Azoren spielt eine wichtige Rolle im westeuropäsichen Westtergeschehen. Im November 2016 ging eine Gruppe um Roy et al. im Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics der Frage nach, ob bei der Ausprägung des berühmten Azoren-Hoch vielleicht die Sonnenaktivität eine Rolle spielen könnte. Ein solarer Einfluss auf diese wichtige Wettermaschine wäre bedeutsam. Und in der Tat stellten die Autoren eine signifikante Kopplung des Azorenhochs an die Sonnenaktivität fest. Sichtbar wird der Zusammenhang vor allem, wenn man die verschiedenen solaren Akivitätskennziffern berücksichtigt, nicht nur die meist verwendeten Sonnenflecken. Es wird immer klarer, dass das solare Magnetfeld eine mindestens ebenso wichtige Rolle spielt, was auch im Fall der Azoren den Durchbruch brachte. Zudem müssen zeitliche Verzögerungseffekte von 1-2 Jahren eingerechnet werden. Das Klimasystem ist träge und springt nicht gleich über jedes Stöckchen das man ihm hinhält. Manchmal dauert es ein wenig, bis sich das System an den externen Signalgeber orientiert und anpasst. Hier der Abstract der spannenden Studie:

Comparing the influence of sunspot activity and geomagnetic activity on winter surface climate

We compare here the effect of geomagnetic activity (using the aa index) and sunspot activity on surface climate using sea level pressure dataset from Hadley centre during northern winter. Previous studies using the multiple linear regression method have been limited to using sunspots as a solar activity predictor. Sunspots and total solar irradiance indicate a robust positive influence around the Aleutian Low. This is valid up to a lag of one year. However, geomagnetic activity yields a positive NAM pattern at high to polar latitudes and a positive signal around Azores High pressure region. Interestingly, while there is a positive signal around Azores High for a 2-year lag in sunspots, the strongest signal in this region is found for aa index at 1-year lag. There is also a weak but significant negative signature present around central Pacific for both sunspots and aa index. The combined influence of geomagnetic activity and Quasi Biannual Oscillation (QBO 30 hPa) produces a particularly strong response at mid to polar latitudes, much stronger than the combined influence of sunspots and QBO, which was mostly studied in previous studies so far. This signal is robust and insensitive to the selected time period during the last century. Our results provide a useful way for improving the prediction of winter weather at middle to high latitudes of the northern hemisphere.